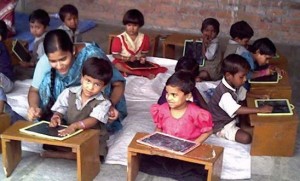

In an attempt to provide an opportunity for improving human capabilities to all children, through provision of community-owned quality education in a mission mode, the Government of India has launched in 2001-02 an ambitious programme called Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), an initiative for universal elementary education. SSA aims to provide useful and relevant elementary education for all children in the 6-14 age group by 2010. Many a times, state interventions are seen as alternatives to market forces. When market fails, the state is requested to intervene. As a broad strategy of SSA programme, the state governments are undertaking reforms in order to improve efficiency of the delivery system. The scheme encourages the states to use ICT and the satellite EDU AT to provide distance education within states to supplement school education with a curriculum base. States too seem to be struggling hard to pitch in making the ICT education integrated to the schools, with a gradual shift of their focus from elementary education to secondary education level. Digital Learning has tried to encapsulate the voices heard from the state heads of the SSA project and the education secretaries, who are marching with the mission of getting kids enrolled and to provide them with the education with innovation.

Dr Alok Shukla, the Education Secretary of Chhatishgarh says, ‘We have many schemes for using IT in education. Under SSA we have started a scheme called “Eklavya Computer aided self learning”. In this scheme fully animated multi-media software has been created based on textbooks of classes 6 to 8. This has been loaded on touch screen computers, and has been kept in the school corridors for easy access by children. Under Indira Soochna Shakti Scheme, free computer education is being given to more than one hundred thousand girl students at secondary level with the help of NIIT. Interactive radio broadcast is being used for teaching-learning of English language at primary level. We have already started using the facility provided by EDUSAT in 50 schools in Koria district. We intend to extend it further to other districts.’ Under the SSA scheme, Rajasthan has embarked on a large-scale education initiative. The initial pilot would have computer learning centers in all state districts to provide elementary education to students. Kerala too is trying to bring in IT in very big way. IT is in the curriculum for students in 8, 9, and 10 standards. For secondary level examination IT is one of the optional subjects, which interested children can opt for. The state provides education to schools in rural areas through EDUSAT. It has also prepared CDs on various subjects, which are meant for middle schools and high schools and is organising live classrooms by telecasting lessons from expert teachers. Jammu too has a multi-dimensional strategy to implement ICT and make ICT a vehicle for transformation of school education. ‘One programme is run under vocationalisation of secondary education and the other is innovative IT component in SSA. We are trying to provide computer labs to higher secondary schools. By the end of the year we must have covered around 350 higher secondary schools,the focus will be to teach computer education as a subject in class 11 and 12. Second is, to provide a cumpulsory computer literacy to every child in higher secondary school, irrespective of whether he/she has taken computer education as a subject or not. We will have acomputer familiarization programme. Initially it will begin from primary classes, and expose them once in a month to common computer practices. And fourth is, computer-aided education and to make that more attractive in primary classes’, says Mohammad Manzoor Bhat, the Education Secretary of Jammu and Kashmir. While the obligation of universalisation of education programme is on state governments, a few NGOs, and some foundations of IT companies too have come forward partnering with government in this direction. Azim Premji Foundation has set up 12,000 computer aided learning centers (CALCs) across India. The Foundation provides curriculumbased learning in the form of multimedia packages and CDs. West Bengal has tied up with IBM to take ICTs to students. IBM is providing the necessary IT infrastructure, education services, IT support and project management for 400 schools initially. Each school is equipped with 10 computers. The schools are expected to train more than 150,000government is also thinking on imilar

lines; teacher training and the development of curriculum and examination system is developed with support from MNCs including Intel and Microsoft. The Rajasthan government is rolling out the UN’sGlobal e-Schools and ommunities Initiative (GeSCI) along with technology companies such as Microsoft, Intel and Cisco. Satyam’s Byrraju Foundation, Airtel’s Bharti Foundation and some other players are very keen in this sector, states like Kerala, Uttaranchal, West Bengal and Rajasthan being proactive in making such partnerships. The programme calls for community ownership of school-based

interventions through effective decentralisation. This is to be augmented by involvement of women’s groups, Village Education Committee members and members of Panchayati Raj institutions. The Programme is having a community based monitoring system. The Educational Management Information System (EMIS) will correlate school level data with community-based information from micro planning and surveys. Besides this, every school is encouraged to share all information with the community. K.M.Ramanandhan, Kerala StateProject Director, SSA, says, ‘Now we are taking the assistance of Panchayati Raj Institutions and we are taking the cumulative planning to school level. Then we have school level work committee member who is very much involved in the planning process. Then we have PTA (parentteacher association), which also help in planning at school level. Once it is done at school level, we consolidate at the panchyat level. Here is a planning and monitoring committee headed by the Grampanchayat president. This committee approves the panchayat education plan.’ But Lida Jacob, while placed as the Education Secretary in the Kerala state, said, ‘To the Education Department and to Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan we give academic support and training. Whether this training is giving them advantage or not has to be monitored. Panchayats can play an important role, but I think we need to make it more systematised. Most of the Panchayat members are graduates and their commitment to education is very high among the elected members of Kerala. We need to channalise it into monitoring the classroom activities. They can provide support to the teaching facilities and infrastructure. SSA is providing funds, trainings, etc. We are trying to ensure that all these funds and programmes are implemented properly and we want to ensure that local bodies play an important role in this process.’ While describing the community role, the state came up with another dimension of implementing SSA programmes effectively. ‘In Kerala, we have started a initiative under the modernising of government programmes called ‘Social Audit’, through community initiative, to improve quality education. Under this scheme, we want schools to conduct their individual self-assessment. Teachers themselves can evaluate their schools in terms of students’ performance, teachers’ performance, infrastructure of the school, etc.’, said Jacob. SSA recognises the critical and central role of teachers and advocates a focus on their development needs. Setting up of Block Resource Centres/Cluster Resource Centres, recruitment of qualified teachers, opportunities for teacher development through participation in curriculum-related material development, focus on classroom processes and exposure visits for teachers are all designed to develop the human resource among teachers. Shyam Shankar Prasad, the Jharkhand State Project Director, SSA, commenting on how the teachers’ training programme in the state works, says, ‘We train teachers through Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU). We have District Institute of Training where we provide training to teachers for 20-30 days. The regular teachers are trained in English language too.’ Considering teachers’ capacity building as the biggest challenge in the direction of  integrating ICTs into the education system under the SSA programme, other hurdles like the problem of connectivity for the last mile in rural areas is also emerging. Despite the market buzz around connectivity for the next billion, not much is happening in rural areas, which still grapple with low teledensity, poor Internet access, etc. For Prasad, ‘The problem is faced more in hilly tracks and in forests areas in Jharkhand, densely populated by the tribal people. We face the difficulty in establishing centres in such places because of lack of infrastructure. We have to shift the schools sometimes to some urban places or most habitated places, may be due to lack of road or lack of school buildings or else to ensure safety to the girls. The difficulties lie with the geographical areas in some districts, which are really difficult to manage with.’ Telecom companies, which have ushered in the mobile revolution in India prefer to stick to cities and tier two towns for broadband access since they find it easier to recover the costs of heavy licensing fees in cities which enjoy a larger subscriber base. There is no incentive for these companies to venture into the hinterland. The Central government’s State Wide Area Networks (SWANs) policy brings a ray of hope to overcome such challenges. This envisages broadband access at the district and block level to solve the connectivity gap. The very success of SSA in getting kids enrolled, and the demographic patterns of India, induces a surge in demand for schooling with a renewed capacity, education with innovation, and making ICT@schools happen.

integrating ICTs into the education system under the SSA programme, other hurdles like the problem of connectivity for the last mile in rural areas is also emerging. Despite the market buzz around connectivity for the next billion, not much is happening in rural areas, which still grapple with low teledensity, poor Internet access, etc. For Prasad, ‘The problem is faced more in hilly tracks and in forests areas in Jharkhand, densely populated by the tribal people. We face the difficulty in establishing centres in such places because of lack of infrastructure. We have to shift the schools sometimes to some urban places or most habitated places, may be due to lack of road or lack of school buildings or else to ensure safety to the girls. The difficulties lie with the geographical areas in some districts, which are really difficult to manage with.’ Telecom companies, which have ushered in the mobile revolution in India prefer to stick to cities and tier two towns for broadband access since they find it easier to recover the costs of heavy licensing fees in cities which enjoy a larger subscriber base. There is no incentive for these companies to venture into the hinterland. The Central government’s State Wide Area Networks (SWANs) policy brings a ray of hope to overcome such challenges. This envisages broadband access at the district and block level to solve the connectivity gap. The very success of SSA in getting kids enrolled, and the demographic patterns of India, induces a surge in demand for schooling with a renewed capacity, education with innovation, and making ICT@schools happen.