IBM KidSmart integrates

technology in early learning Some 20 elementary school teachers in Philippines underwent a 3-day training on the IBM KidSmart Early Learning Programme, intended to improve teaching-learning performance. The goal of IBM’s technology enhanced early learning programme is to support early childhood educators who are trying to ‘reinvent education’ through meaningful use of new technologies in childcare centers and early grades classrooms. Over the last five years, IBM Philippines has invested in various education and community-based projects to intensify training for blind students.

USD20 million e-Asia

partnership fund at ADB The Government of the Republic of Korea has set up a USD20 million e- Asia and knowledge partnership fund at ADB. The fund aims to bridge the digital divide and promote access to information and creating and sharing of knowledge through Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) in the Asia and Pacific region. The e-Asia programme will support projects that aim to reduce and bridge the digital divide and the Knowledge Partnership programme will support projects that aim to strengthen communication technologies -based distance education and e-learning are key components. China now has three of the world’s mega-universities in which over 100,000 students use largely distance learning methods. By the end of 2004 some 94 million people in China were online, almost half of them with broadband access. China has a network of independent radio and television universities coordinated by the China Central

Radio and Television University. A new model for distance education in Asia

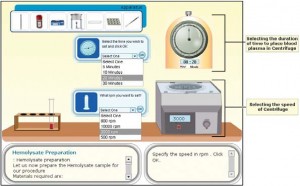

In Asia, distance education using information and communication technologies (ICTs) is proving to be an efficient way of delivering highquality

education using course materials often developed by the best faculty teams. Naveed A. Malik, rector of the Virtual University of Pakistan, is leading a project to develop a model for distance education that can be used in various Asian countries, with support from Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC). Launched in 2005, the PANdora project, as it is known, is involving researchers from 11 countries (Cambodia, China [Hong Kong], India, Indonesia, Laos, Mongolia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Viet Nam) in the investigation of a broad range of issues.

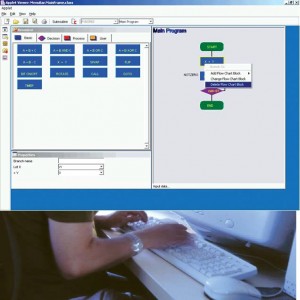

Researchers for example, are looking at how short message systems (SMS) could be used to handle student registration; evaluating various kinds of distance learning software; sharing learning objects; and analysing how to rigorously e-assess students’ work to ensure high standards. the capacity of developing member countries, through workshops, trainings, research work, and publications.

Internet network to support education in Thailand

The Information and Communications Technology Ministry of Thailand has established a high-speed international Internet network to support the research and development and education sectors and to enhance the skills of the researchers and students at universities in Thailand. It will link up with TEIN2 (Trans- Eurasia Information Network), built by the Delivery of Advanced Network Technology to Europe (DANTE), a European non-profit organisation. TEIN2 provides a continuous and consistent environment for electronic collaboration for research and education between Europe and the Asia-Pacific region.

TM Net to promote broadband in schools

Internet service provider TM Net in Malaysia hopes that its plans to increase broadband customer base by 400,000 this year will attract more students to subscribe to its edubroadband content application and access services. This will further help to promote the use of broadband content and applications in schools. TM Net’s ultimedia in Education Malaysia can help guide them on the techniques of e-learning. As at end of last year, the service provider had 495,000 Streamyx (TM Net’s broadband service) subscribers. TM Net currently has more than two million dial-up users, and the challenge now is to convert them to broadband.

Interactivity depends very much on the cultural makes of individuals; some are more reserved while others are more ready to participate in group discussions. Hence, the portal caters to this diversity of student groups to bring them up gradually to the public discussion forum.

Interactivity depends very much on the cultural makes of individuals; some are more reserved while others are more ready to participate in group discussions. Hence, the portal caters to this diversity of student groups to bring them up gradually to the public discussion forum.