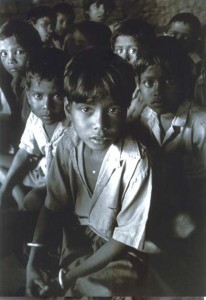

Seva Mandir, an NGO working in 161 villages of Udaipur and Rajsamand districts of Rajasthan, India, has initiated an interesting experiment to reduce teacher absenteeism using a camera to record the presence and attendence of teachers in the classrooms which determined the teachers a pay, the organisation not only reduced teachers absenteeism but also improved students performance. This article discusses in detail this experiment towards improving the quality of education for children, especially those marginalised by the mainstream education system

Context of Udaipur region

Udaipur region of Southern Rajasthan in India is mostly hilly, with large parts of the hills now being barren. The natural resource base is highly degraded consisting of agricultural land, forests, pasturelands and wastelands. Most of the land is owned by the Government and are degraded and poorly managed. Due to the inadequacy of the natural resource base in providing ample livelihood options, most families engage in physical labour outside their villages. The local population also fares poorly on indicators of health and education.

Background of Seva Mandir’s education programme

Seva Mandir started its work in the 60s with adult education. Over the time, the focus of Seva Mandir’s education programme shifted to children’s education, especially for those marginalised by the mainstream education system. As part of this, it is running 174 rural schools. An evaluation of these schools done in 1995-97 showed that the schools were not faring very well on children’s learning abilities. The main reasons for that were related to the teachers’ own academic competencies and the pedagogy they used in the classroom.

For the last 6-7 years, Seva Mandir has invested a lot to enhance the teachers’ own abilities and their understanding of children’s learning processes. This has led to improvement of the teacher’s abilities and motivation thereby impacting positively the children’s learning and enrolment. Some meaningful partnerships have been forged with external agencies for this work, like the Vidya Bhavan Society.

Objectives of Seva Mandir’s education programme •

Provide quality education, to enable children in the age group of 6 to 14 years who are deprived of education to independently read and write with comprehension • Create spaces which allow people to recognise and articulate the need for an alternative, higher quality and more meaningful form of education Why the camera experiment? As said above, by and large the teachers are fairly motivated and the children in these schools are also doing well in their studies. Yet, in these schools also teacher absenteeism has been a concern.

Teachers often would not come to school without giving any prior information. The organisation therefore was looking for ways to reduce this absenteeism, looking for ways, which would not increase patronage between the monitor and the teacher. It was in this context that the idea of using a camera came from Prof. Esther Duflo of Massachusettes Institute of Technology (MIT). Seva Mandir had an old relationship with MIT and it decided to conduct an experiment to see the impact of cameras on teacher presence.

About the experiment

About the experiment

120 schools were selected to participate in the study, of which the camera was given to 60 randomly selected schools (the “programme schools”). The pictures taken at the start and end of each working day were used for determining teacher attendance, and thus determining teacher pay.

The monthly base salary was set at INR 1,000 for 21 days of work in a month. Teachers received a bonus or a fine (INR 50 per day) for days more or less than the number of “valid” days where they actually attended. A “valid” day was defined by a day where the opening and closing pictures were separated by at least five hours and the number of children in both pictures was sufficient to indicate that children were present (at least eight).

The fine was capped at INR 500; hence, a teacher’s salary could range from INR 500 to INR 1,300. In the remaining 60 “comparison” schools, teachers were paid INR 1,000, and were told as usual that they could be dismissed for poor performance. The payments were made on a bi-monthly basis. Each school in both the treatment and the control categories received one unannounced visit per month (“random check”). The enumerator noted whether the school was open or closed, how many children were in class at the time of the visit, and what the children and the teacher were doing. In collaboration with Seva Mandir, the evaluation team (MIT and Vidya Bhavan) conducted three exams, in August 2003 (at the start of the programme), April 2004, and September 2004.

The tests covered basic Hindi and ath competencies. The first test followed the usual methodology: children were given either a written exam (for those who could write) or an oral exam (for those who could not write). For the post-test and the mid-test, both the oral and written exam was administered to all children. Children who were unable to write received a zero score for the written sections.

Results of the experiment

Prior to the programme, school and teacher quality was similar for the programme and comparison schools. Before the programme wasannounced, the attendance rate was 66 per cent and 63 per cent, respectively. However, this threepercentage point difference is not significant. Other measured aspects of school quality were also similar (number of students present at the time of visit, infrastructure, teacher qualification).

Student academic performance was similar across the programme and Camera was given to 60 randomly selected programme schools. The pictures taken at the start and end of each working day were used for determining teacher attendance, and thus determining teacher pay. comparison schools prior to the programme. A pre-test exam was administered to the 2,230 students enrolled in all 120 non-formal education centres in September 2003. In the pre-test, 17 per cent of children in the treatment schools and 19 per cent in the comparison schools took the written exam (the difference is not significant).

Those who took the oral exam were somewhat worse in programme schools though the difference is not significant, and those who took the written exam were somewhat better in treatment schools.

Teacher absence and teaching

activity The impact of the incentive programme on absence was large and immediate, as measured by randomcheck data. In September 2003 teacher attendance increased relative to August in programme schools, and decreased in comparison schools. Between September 2003 and October 2004, teacher absence was, on an average, 18-percentage points lower in the programme schools than in the comparison schools. Thus, the programme halved absence rates in treatment schools.

This reduction in absence is due to both, some teachers starting to attend work all the time and to a complete elimination of entirely delinquent teachers those who come less than half the time. Subsequent to the implementation of the programme, the total number ofchildren found in open schools did not differ between programme and comparison schools.

However, the fact that programme schools are open more days should result in a larger number of days of teaching per child. The children-days measure is constructed as number of children who are found in class at a random check if the school is open, and zero if the school is closed. On average, three more children are present in a programme schools, increasing the number of children-days by roughly 30 per cent. Assuming there are about 27 days of work in a month, this figure translates into 88 more children-days of instruction in the programme schools.

Effects on learning

Effects on learning

Children in treatment schools got an average 30 per cent more instruction time than children in comparison schools. Did this result show an increase in test scores? To minimise the impact of attrition of children on the study, considerable attempts were made to track down children who were not present at the mid- and posttest, and to administer the post-test to them. In total, out of the 2,230 students who took the pre-test, 1,893 took the mid-test, and 1,760 took the post-test.

The test data reveal that the programme had a significant impact on learning, even as soon as the mid-test is over. In the mid-test, children in treatment schools gained 0.11 standard deviations of the test score distribution in language, 0.15 standard deviations in math, and 0.17 overall. Children with higher initial education levels gained the most from the programme: children who took the written pre-test have test scores that are 0.25 standard deviation higher in programme schools than in comparison schools at the mid-test. Overall, after one year in the programme, children learned significantly more in treatment schools than in comparison schools.

In the post-test, children in treatment schools gained 0.15 standard deviations of the test score distribution in language, 0.16 standard deviations in math, and 0.17 overall. As in the mid-test, most of the gains in learning levels can be attributed to children with higher initial education levels. It can be said at last that the monitoring system through cameras linked with financial systems helped reduce absenteeism in Seva Mandir schools.

This point is important that in Seva Mandir’s case, it led to improvement in learning levels. Even in programme schools, if there had been no efforts at improving quality across the schools, it is not very sure if increased presence of the teachers would have led to increased learning The monitoring system through cameras linked with financial system helped reduced absenteeism in Seva Mandir Schools. It led to improvement in learning levels too levels of the children.

Also, the fact that the system of using photographs to calculate payments was rigorously used helped instill the teachers’ faith in the system. If the system had been misused to tamper payments, there is no certainty if the teachers’ would have cooperated in letting the experiment go on. In the above experience, “quality education” has many components, of which teacher presence is only one. The camera project has helped establish the fact that teacher absenteeism can be reduced using creative methods.